How Scientific Virtual Assistants Differ from Alexa

- fredericbost8

- Mar 30, 2021

- 6 min read

“How is this different from Alexa?”

It’s something we hear quite a bit, and rightfully so. With the explosion of virtual assistants in our everyday lives over the past decade, most people - scientists included - have never encountered voice tools other than Alexa, Siri, or Cortana.

In this article, we’ll take a closer look at some of the differences between Alexa and tools like LabVoice that allow our platform to excel where consumer devices come up short in the lab. And there are indeed some similarities that we should mention as well, so we’ll touch on those.

Difference #1: Scientific voice assistants are looking for scientific answers.

Alexa and other every day voice assistants are designed to expect a number of different prompts and have to be prepared for anything. Think about it: in your day-to-day, you probably engage Alexa with a variety of questions and commands: “What’s the weather today?” “What’s on my calendar” “What was the score last night?” “Tell me more about COVID-19 vaccinations roll outs.” To their credit, the team at Amazon has gotten really, really good at expecting such a broad range of outcomes, but we’ve all experienced times when Alexa has tripped up and completely misunderstood us. This misunderstanding is due to the device’s expectations that anything could be asked of it.

If you say the word “cents”, for example, Alexa may not completely understand the context in which that word was used, and has to run through every possible word that “cents” could be: “cents”, “scents”, “sense”, or “cense”. And it has to do this for every word and every syllable. Something like “dichloromethane” could easily cause Alexa to inaccurately record what the user had said.

Scientific voice assistants are able to improve accuracy by narrowing the range of expected possible answers. That is to say, these voice assistants “know” they’re being used in a scientific setting, and through backend tools, favor those expected answers. The ability to self-correct towards these types of answers is crucial, given the importance of data integrity. And specifically with our platform, if LabVoice is not confident that it heard the user correctly, it can ask the user to confirm their answer (“Did you mean ‘dichloromethane’?”).

Difference #2: Alexa, for the most part, is really an “out-of-the-box” tool.

“Set a timer for 10 minutes.” “Remind me to order more gloves.” “What’s 9 nanoliters in cubic centimeters?”

Alexa is really useful for atomic actions, especially in the kitchen when cooking. These actions are likewise useful in the laboratory, when hands are full of samples, animals, plates, or more and researchers need to get their thoughts or measurements down ASAP.

The challenge with everyday voice assistants arise when you begin to try and string these types of commands together; in other words, try to create a more tailored experience. It feels unnatural to keep saying “Alexa, do this” for shorter requests.

Let’s look at a cell counting process to illustrate the point. Here’s what the exchange would look like if the users was trying to use Alexa to capture only the Donor ID and number of cells:

User: Alexa, take a note.

Alexa: Ok, what should I note?

User: The Donor ID is 123 and the cell count is 54.

Alexa: You want me to note “The Donor ID is 123 and the cell count is 54,” right?

User: Yes.

Alexa: Ok, noted.

User: Alexa, take a note.

Alexa: Ok, what’s your note?

User: The Donor ID is 124 and the cell count is 67.

Alexa: You want me to note “The Donor ID is 124 and the cell count is 67,” right?

User: Yes.

Alexa: Ok, noted.

User: Alexa, take a note.

Alexa: Ok, what’s your note?

User: Donor ID 124’s vial was damaged.

...you get the point. There’s a lot of wasted time and it’s not really efficient. And as we mentioned before, if the user wants to add additional observations, the likelihood a consumer-oriented voice tool would misunderstand their intention is high, especially pertaining to scientific vocabulary.

It would be great to easily tailor this specific process to the scientists’ workflow. If you were lucky enough to have the time to build your own process, you’d see that the tools Amazon Web Services (AWS) offers are geared towards people with backgrounds in coding. There’s a learning curve to using these tools that many scientists don’t quite have to invest in, cutting significantly into the ROI of using voice.

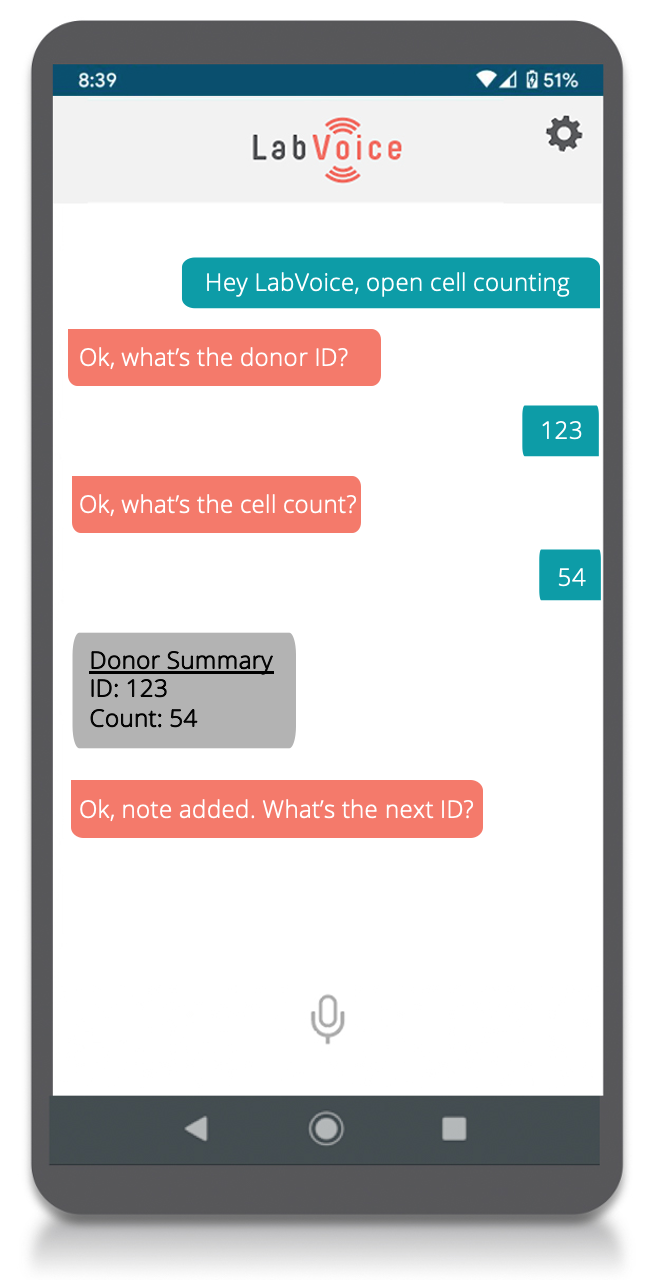

With scientific voice assistants, users are able to easily optimize their processes to streamline results collection. With LabVoice in particular, users have the ability to request that the LabVoice team build these workflows for them (in just a few hours) or make the changes themselves. They can control the speed in which LabVoice responds, whether or not its prompts need to be relayed audibly (with the mobile app, users can follow along on the screen), and many more features to improve the speed in which they go through the process. You’ll notice in the below example that there’s no need to prompt LabVoice each time, as LabVoice is automatically listening

to that authenticated user when engaged.

User: Hey LabVoice, start cell counting.

LabVoice: Ok, what’s the donor ID?

User: 123.

LabVoice: Ok. What’s the cell count?

User: 54.

The user has a variety of commands at his or her fingertips as well: “Done”, “Pause”, “Add a note”. Scientific voice assistants will understand these with ease, structure the data in an easy-to-digest format, and save countless hours of frustration by eliminating accuracy issues and double data entry.

Difference #3: Alexa was not designed for noisy environments.

The home can be a loud place. Babies crying, dogs barking, vacuums whirring, dishes clanging, water running. That being said, your oven’s exhaust fan or vacuum is probably the loudest piece of equipment in your home, and Alexa knows that. It operates fine in these scenarios.

But throw Alexa on the laboratory floor with vacuum pumps and industrial filtration systems, and you’ll find the performance drops significantly. Throw in a user behind a face mask and shield, and the performance weakens. The Amazon suite of microphones and speakers were simply not built for the lab environment.

Scientific voice assistants, for the most part, are able to filter out background noise through a variety of backend technology that they use. If you haven’t seen an example of this already, we have a video illustrating our voice assistant in action in a lab.

But even that technology will meet its limitations, which is why we give access to the voice assistant through a mobile application. That way, whether equipment is just too loud or users are muffled through their protection equipment, a boom mic headset & mobile application will ensure that users can hear their voice assistant, and it can hear them.

Difference #4: Where do I access all this captured data with Alexa?

Data collection is one aspect we’ve tangentially touched upon, but haven’t really looked at in much detail.

With technology like Alexa, users are indeed able to capture observations, parameters, data points, and more, but once collected, how do they access that? It’s quite easy to have this information relayed in the Alexa app or sent via email, but that will require formatting to save in the proper database, and in some cases, may be heavily reliant on the user to interpret those data points several hours after they’ve completed the work. And, it’s not an easily validatable tool, if there was ever a requirement or need to perform such qualifications.

Scientific voice assistants place a heavy emphasis on data capture and configuration, and as such, have numerous means lessening the burden on the scientist to manually manipulate and/or post data to other locations. At a minimum, scientific voice assistants should be able to configure data in a tabular format with complete audit logs and export in multiple formats (csv, excel, pdf, word doc, etc). These tools should always offer the option to be validated, even if that’s not a requirement for your lab at that time.

At LabVoice, we’ve placed an emphasis on integrating with informatics tools and other data management systems. While we can actually save data, we want to avoid creating data silos and push our customers to integrate LabVoice with their ELN, LIMS, or SDMS (in whatever form those tools take shape). Visit our Partners page for more information on our integrations.

Similarities

There are a lot of things Alexa, Siri, and the other voice assistants in our everyday lives do really well, and we’ve adopted them into our platform. For example, both tools support a variety of languages and accents, with the ability to switch between languages and more. As previously mentioned, atomic actions (timers, reminders, notifications, etc) are helpful. And it doesn’t hurt to be able to tell a joke or two when in the midst of a long day.

When thinking about evaluating voice in the lab, scientists should always consider adopting tools built for that scenario. We’re happy to offer a no-cost prototype of a voice-enabled process, so please get in touch with us if you’re interested at info@labvoice.ai, or chat in the corner.